If the moral calculation is simply, "Did the ends justify the means?" it's hard to see why we even bother with laws in the first place.

-- Chris Hayes (Wednesday)

No exceptional circumstances whatsoever, whether a state of war or a threat of war, internal political instability or any other public emergency, may be invoked as a justification of torture.

-- The United Nations Convention Against Torture (1984)

Should any American soldier be so base and infamous as to injure any [prisoner] ... I do most earnestly enjoin you to bring him to such severe and exemplary punishment as the enormity of the crime may require … for by such conduct they bring shame, disgrace and ruin to themselves and their country.

-- George Washington (1775)

This week's featured post is "5 Things to Understand About the Torture Report". A couple of Sift milestones: I moved the Sift to WordPress and started trying to upgrade it in June, 2011. The WordPress stats inform me that the blog is one recent-average-week away from its 1 millionth page view. Also, the 4,000th comment happened last week.

This week everybody was talking about torture

My comments on the Senate's torture report are in "5 Things to Understand About the Torture Report".

But the public debate about the report was also illuminating. By coincidence, the report came out in the middle of a cycle of protests against police violence, emphasizing how quickly conservatives can flip-flop on government power. It's tyranny to do a background check on gun-buyers. It's tyranny to make people buy health insurance -- a step towards the ultimate tyranny of making them eat broccoli. (My Mom was just like Hitler that way.) But when the agents of government power shoot unarmed black men on the street or torture someone in a secret off-shore prison, that's just dandy.

One of my Facebook friends brought the proper descriptive term to my attention: herrenvolk democracy. Herrenvolk is the German term that usually gets translated "master race". So herrenvolk democracy is the belief that democratic principles are wonderful as long as you restrict them to the right people. As in: I have the right to carry a gun in public, but it's fine if police shoot down John Walker. I have habeas corpus and due process rights, but it's OK to drive Jose Padilla insane by holding him in sensory deprivation for three years without filing charges.

One of my Facebook friends brought the proper descriptive term to my attention: herrenvolk democracy. Herrenvolk is the German term that usually gets translated "master race". So herrenvolk democracy is the belief that democratic principles are wonderful as long as you restrict them to the right people. As in: I have the right to carry a gun in public, but it's fine if police shoot down John Walker. I have habeas corpus and due process rights, but it's OK to drive Jose Padilla insane by holding him in sensory deprivation for three years without filing charges.The ultimate American herrenvolk democracy was the Confederacy, whose flag tea partiers love to wave. It zealously defended the democratic rights of white people, including their right to own black people. In today's vision of herrenvolk democracy, the "right people" aren't always so clearly defined as white vs. black. But whenever someone starts talking about "real Americans", that's what they mean -- not everybody who is technically a citizen, but the much smaller group of Americans who ought to have freedom and a voice in government: the Herrenvolk.

and avoiding another government shutdown -- for a price

True to their word, Mitch McConnell and John Boehner didn't shut down the government again. But they did extract some ransom on behalf of their clients on Wall Street.

The budget deal that passed Saturday night contained a number of what are called "policy riders" -- changes in the law that have nothing to do with the spending and taxing a budget is supposed to be about. This is a prime way for Congress to give special interests unpopular favors, by attaching them at the last minute to a bill that has to pass.

Maybe the worst special-interest rider repeals Section 716 of the Dodd-Frank financial reform package that was passed to keep the 2008 financial catastrophe from happening again. The blog Next New Deal has the details:

Section 716 of Dodd-Frank says that institutions that receive federal insurance through FDIC and the Federal Reserve can’t be dealers in the specialized derivatives market. Banks must instead “push out” these dealers into separate subsidiaries with their own capital that don’t benefit from the government backstop.

In other words, Dodd-Frank used to say that banks couldn't make big, risky bets, keep the profits if they win, and stick taxpayers with the bill if they lose. Congress just repealed that.

Who would draft such a law? Citicorp.

and the University of Virginia rape story

I'm sure Rolling Stone and Sabrina Rubin Erdely meant well. Campus rape is a problem in need of a poster girl, so they provided one: "Jackie" from the University of Virginia, a September freshman who is lured into an upstairs bedroom by her date "Drew", and then gang-raped in some sort of frat initiation ritual. Her friends discourage her from reporting it. ("She's gonna be the girl who cried 'rape,' and we'll never be allowed into any frat party again.") And when she does get around to telling her story to UVA officials at the end of the year, they seem more interested in protecting the school's image than in seeing justice done. ("Nobody wants to send their daughter to the rape school.")

That story is the horrifying scaffolding on which Erdely hangs many true and important facts and statistics about campus rape -- numbers that by themselves are too lifeless to publish in a glossy magazine, and wouldn't go viral online like Erdely's article did. That's what good stories do: pull dry facts together into something that has emotional punch and demands action.

The problem? The writer and editors didn't do basic fact-checking on Jackie's story. When The Washington Post did, a bunch of details didn't hang together. That started a backlash, in which one slimeball released what he says is Jackie's real name.

Personally, I still believe the core of Jackie's story. But Erdely should have known that this is exactly the kind of situation where memories drift: Jackie bottled up her traumatic story for an entire academic year, then got involved with a rape-survivor group that caused her to retell it many times. In such settings, people have a tendency to remember previous tellings of their stories rather than the actual experiences. (My childhood memories aren't all that traumatic, but I can tell they've drifted. Occasionally I remember some event with HD clarity, then realize the room I'm picturing it in wasn't built yet.)

So in the end, Erdely succeeded in making Jackie a poster girl, but for the bitches-be-lying chorus. Years from now, women who go public with a campus rape will be confronted with "that Virginia girl who made the whole thing up".

Thanks, Rolling Stone. Journalism in the wrong hands can do a lot of damage.

but let's talk about books

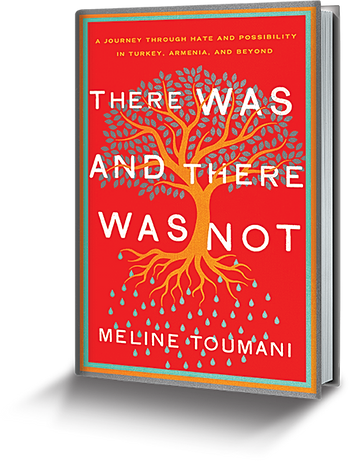

I just finished reading a new book that could be a good basis for discussion about race and prejudice and privilege: There Was and There Was Not by Meline Toumani.

I just finished reading a new book that could be a good basis for discussion about race and prejudice and privilege: There Was and There Was Not by Meline Toumani.Toumani is an Armenian-American who was born in Iran. Growing up, her identity as an Armenian is shaped around the genocide of 1915, and Turks are villains of near-mythological status. But as a young adult, she begins to wonder whether this focus on Armenians' historical victimhood is doing them any good. Eventually she hatches a plan: She will go to Turkey, learn Turkish, and see if there isn't some way everybody can live together in peace. This leads to one of the best opening lines I've ever read:

I had never, not for a moment, imagined Turkey as a physical place.

Her two years in Turkey are a lesson in the complexity of ethnic conflict, which is both more and less tractable than she had imagined. The Turks are not monolithic, and she easily relates to the other ethnic minorities: Kurds, Jews, and even the few remaining Armenians. Among the ethnic Turks, some are nationalistic and anti-Armenian, some are open-minded and egalitarian, and most are basically decent people who have never thought very hard about the slanted history they were taught in school (where Armenians are the villains of 1915 and Turks the victims) or the unfair advantages Turkish society gives them over Kurds, Jews, and Armenians.

The countryside is beautiful, Istanbul is exciting, and the culture has many charms. And yet ... Toumani is always a second-class resident. Her Armenian-ness hangs in the background of every social interaction as something to be confessed and explained. (She looks more Turkish than American, but speaks with a foreign accent. Where is she from really?) The Turkish attempt at color-blindness ("We are all Turks") is more obliterating than accepting. And even when the government preserves bits of Armenian history and culture (Armenia was a regional power from antiquity until around 1000 AD) the ethnic adjective Armenian is replaced by the geographical adjective Anatolian, as if some nameless people had occupied this land before the Seljuk conquest.

She sees another side of prejudice when she attends the pan-Armenian games in Yerevan. When the competitive juices get flowing, the anti-Turkish slurs Armenians have repeated since birth are easily brought out and used against the team from Istanbul, even though they belong to the Armenian diaspora as much as the Parisians and Argentinians do.

Toumani realizes it is time to come home to America when she recognizes her own case of Stockholm Syndrome: She has begun to internalize her second-class status. Immersion in Turk-dominated society is making her yearn for the approval of the ethnic Turks and treat them as the masters.

I can't read this book through Armenian or Turkish eyes, but as a white American I find it worthwhile precisely because I have no dog in this fight. Issues of bias and historic victimhood and systemic privilege are fraught with guilt, anger and other emotional baggage when Americans try to think about them in our own historic context of black and white. Toumani has given us a rare opportunity to watch similar conflicts play out in a context where we can be more objective.

Daniel Sillman interviews Matthew Avery Sutton, author of the new book American Apocalypse. Sutton re-interprets Evangelical Christianity for us outsiders, and claims we've grossly underestimated the importance of believing Jesus is coming back any day now. Oversimplifying just a little: Mainstream Christians are liberals because they're trying to build the Kingdom of God on Earth. Evangelicals are conservatives because they think the Antichrist is about to take over.

Daniel Sillman interviews Matthew Avery Sutton, author of the new book American Apocalypse. Sutton re-interprets Evangelical Christianity for us outsiders, and claims we've grossly underestimated the importance of believing Jesus is coming back any day now. Oversimplifying just a little: Mainstream Christians are liberals because they're trying to build the Kingdom of God on Earth. Evangelicals are conservatives because they think the Antichrist is about to take over.[T]he apocalyptic theology that developed in the 1880s and 1890s led radical evangelicals to the conclusion that all nations are going to concede their power in the End Times to a totalitarian political leader who is going to be the Antichrist. If you believe you’re living in the last days and you believe you’re moving towards that event, you’re going to be very suspicious and skeptical of anything that seems to undermine individual rights and individual liberties, and anything that is going to give more power to the state.

Well, except giving government the power to control reproduction. Maybe the full book explains that.

and you also might be interested in ...

The Democrats' problems with the white working class may make more sense that What's the Matter With Kansas? would have us believe. Thomas Edsell lays out a simple narrative, which I'll summarize: A generation ago, the unspoken social contract of the white working class was that they would acquiesce to class oppression if they at least got the benefit of racial oppression. By fighting for racial equality while letting class inequality get worse, Democrats broke that agreement. Now the white worker has to compete with non-whites at home and abroad, but is also under his boss' thumb even more than in the past.

That sense of victimization comes out as resentment of non-whites, which on the surface makes no sense, because whites still have unfair advantages. But the real root isn't "Those people have it better!", it's "We had a deal!". The terms of that deal are indefensible (because racism is indefensible), so it can't be argued in public or even consciously acknowledged. But the resentment is still there.

While I've been working on a big mythic vision for liberalism, Mark Bittman is taking more of a bottom-up approach: Can we link together all the movements that are getting people into to the streets? How do we see raising the minimum wage, unionizing Walmart, controlling the police, taking the country back from Wall Street, and fighting climate change as one big movement?

Think Progress published a list of 21 non-white or mentally ill people who have been killed by police under questionable circumstances in 2014.

It's worthwhile to remember that police don't have to shoot down even people who are armed and uncooperative ... if they're white.

Whenever there's an unusual weather-related event, people start asking whether climate change "caused" it. Slate's Eric Holthaus explains why that's a dumb question, with the California drought an example.

I'm a sports fan, so I make sports analogies. In 2001, when he was turning 37 and should have been just about over the hill, Barry Bonds hit a record 73 home runs, having never hit more than 46 homers in a season during his prime. The common explanation is steroids. But still: It makes no sense to look at any one of those 73 homers and ask whether steroids caused it. Barry was a power hitter before the steroid era. Maybe this particular home run is one he would have hit anyway.

Ditto with droughts, hurricanes, and the like. Climate change juices up bad weather events. Without it we'd still have some, but not as many and not as bad. Is this particular event one of the extra ones? Until we establish communication with parallel universes, there's no way to know.

I only know one exception to that rule: If climate change raises sea level by a foot, then it makes any storm surge a foot higher. If you live near a coast, that may determine whether you get flooded or not.

Chris Mooney explains why the price of oil is crashing: Not so much an increase in supply as a slow build-up of supply followed by an expected decrease in demand. Kevin Drum thinks this is very good news for the economy.

and let's close with something silly

No comments:

Post a Comment